Azeri Traditions for Bayram; Seeing in the new year with a happy home & heart

Part 4: Fire or Akhir Charshanbasi - Fire fun & fortune

The most fun, exciting, and dangerous of all Bayram preparations takes place on this eve, when we leap over fire to cleanse ourselves and burn away bad luck before the new year, saying:

آتیل باتیل چهارشنبه بختیم آچیل

Azerbaijan was on the path of our human journey east out of Africa and this area has been inhabited ever since. It has had many names over this period. Fire is ot in Turkic languages and azar in Iranian. With natural gas huffing out of the ground and igniting, it’s no surprise that Azerbaijan is known as the Land of Fire! There are many theories about the name "Azerbaijan": some postulate it comes from the name of an ancient ruler, others that it is related to the origin of the word Asia, and of course, there are many associations with fire. Azerbaijan is also thought to be the birthplace of Zoroaster. We cannot be certain, but in a place now known as Sooghurli, or Takht-e Soleyman, a sacred, high-grade fire was kept in the temple of Adur Gushnasp (آذرگُشنَسپ). Since the 5th century, it has been mentioned in texts as a place of Bayram and Sadeh festivals.

Fire gives and takes life. Volcanic soils are nutrient-rich, fire stimulates some seeds to germinate, and we use it for light, heat, warmth, cooking, and protection. But it can also be destructive. Wildfires, once rare in Central Asia, are now burning the steppes of Kazakhstan, threatening the ecosystem. Since these lands were abandoned, the grasses that were once grazed are now like tinder, catching fire easily. Although the Saiga antelope population has been increasing after near-extinction, it’s still not the same as the seasonal grazing of sheep, goats, and horses on a large scale. The grass seeds here can withstand low-intensity fires, but not with the frequency they are now experiencing.

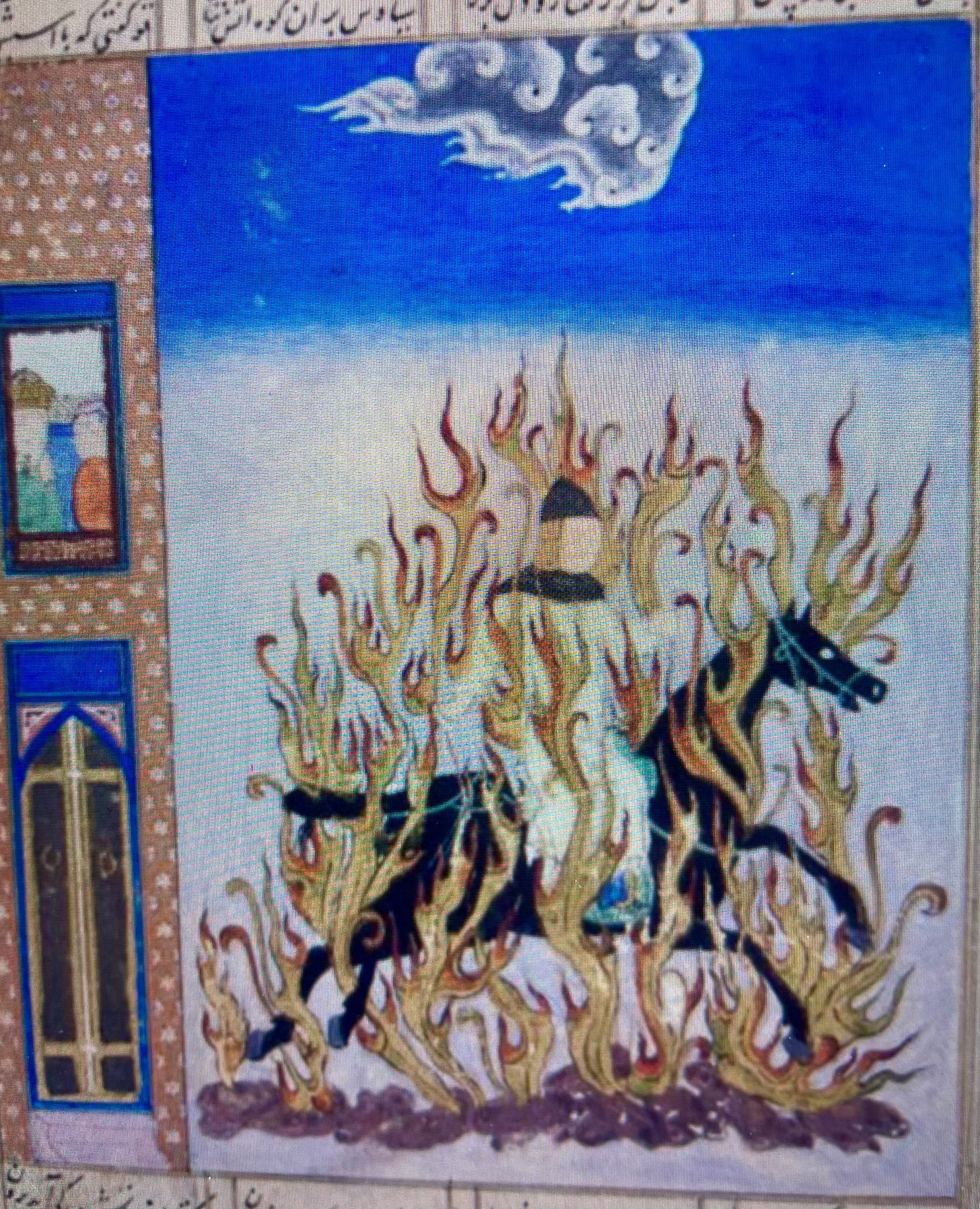

Throughout this series, I’ve shared traditions I have personally witnessed, with so many different peoples celebrating Bayram, there are countless customs, similar, yet distinct, across the region. Here are my traditions for Akhir Charshanba(اخیر چارشنبه) in Azeri and Chaharshanbe Soori (چهارشنبه سوری) in Iranian. Soor can be translated as fire or red, and in one account I read, it is even said to be the root of the word "surprise." The story comes from the Shahnameh, the 10th-century Iranian epic by Ferdowsi: Siavash, to prove his innocence, jumped through fire on the last Wednesday eve of the year. His father, Kaykvus, celebrated his son’s victory by giving his subjects a soor, a joyful surprise!

Around this time of year, in many cultures and religions, there are themes of coming back to life and resurrection, which we know as dirilanmaq. Similarly, we believe in the power of the sun (with more daylight) and fire to bring life and rebirth at this time. Some, like a phoenix, rise from the ashes; others, from the earth. Around this Charshanba, we visit the graves of our dead. Linear time doesn’t diminish what we hold dear in our hearts. In essence, what I’ve been writing about these past few weeks has been about the passing and marking of time, and honouring what is precious.

A fun Azeri tradition: Shal Salmakh! Shahriar says:

!هرکس شالين بير باجادان سوْخوردى آى نه گؤزل قايدادى شال ساللاماق

Everyone drops their scarfs into a hole /chimney

What a lovely custom it is to drop scarves!

Similar to leaving stockings to be filled at Christmas, on the eve of Akhir Chaharshanba, youngsters tie several scarves together to make one long scarf. Then, they throw it over a neighbour's wall or dangle it down in front of a window from flat rooftops. Afterward, they make noise to alert the homeowner. The homeowner, who is expecting these scarves, fills the end with whatever treats they have, ties it up into a bundle, gives the scarf a tug, and the kids pull it back to retrieve their surprises, to their absolute delight.

Some say these gifts each carry meaning: a loaf of bread symbolizes fortune, sweets bring happiness, and walnuts promise longevity, just to name a few.

I’ve mentioned khoncha in my piece about Chilla Jejasi. A khoncha is a tray or basket filled with gifts for new brides, fiancées, and daughters. Traditionally, it would be put together with great love and filled with Bayram-related items such as shakar bura, sumani, flowers, coloured eggs, fresh and dried fruit and nuts, and fabric for dressmaking. These days, khoncha often contain ready-to-wear clothes, scarves, mobile phones, and chocolates , delivered either by the family or even courier services.

My dear aunt Manizheh (may her soul be happy) would buy small packs of uzarrih (Peganum harmala — the seeds burned to purify the air and ward off the evil eye) and a small mirror for ishikhlukh (to bring light and reflection), and gift them to family and friends on this day.

All these things are bought at the bazaar, which is usually brightly lit and beautifully decorated for Bayram. We buy many things from temporary street vendors, some of whom bring their homegrown or handmade wares to the big cities. You can find almost anything — even sprouted greens, in case you forgot to grow yours. People also buy live goldfish, which, though traditional, feels quite cruel since they’re usually kept just for a week and rarely survive long after.

The banks are packed with people eager to exchange money for brand-new, crisp notes to give as gifts. Printers are busy too, producing wall, desk, and small calendars for businesses, beautifully designed and gifted to their best customers, friends, and family.

In the days leading up to Akhir Charshanba, people begin gathering materials for the bonfires. In the past, these fires were lit on rooftops or in the mountains by a young boy using flint stones.

For centuries now, people have gathered, built fires, and jumped over them in a symbolic act of cleansing and wishing for good fortune. Based on my research, we aren’t entirely sure when fire-jumping began, whether it has roots in ancient traditions or more likely developed during the post-Islamic period.

Since the we started harnessing fire, we have gathered around the hearth. I often read about Zoroastrianism and how its followers are called “fire worshippers,” probably translating from the Iranian term Atash Parast. However, parast, although now commonly understood as “worship”, actually means “to stand around.” I also imagine that Zoroastrians would find it disrespectful to jump over fire. And as I mentioned in Part 2 of this series, this tradition may have originally involved jumping over water, a custom that still continues in some places.

All over the region, regardless of age, people gather outdoors with family and friends, making fires, usually in a row of seven. Just like Siavash, we jump for joy. Depending on where we are from in Iran, we ask for something different from the fire: either to burn away bad luck and bring good fortune (in the Turkic tradition), or for its rosy glow to replace our winter pallor (in the Iranian tradition).

It goes without saying, though, that there are many injuries and accidents on this day, so much so that some people call it Chaharshanbe Soozi (Burning Wednesday). Much like Bonfire Night in the UK, things can go wrong for the more reckless pyromaniacs among us.

All the fire-making and jumping around makes us a bit peckish, so we snack on Akhir Chaharshanba yemishi — a mix of dried fruit and unsalted nuts. Each home has its own blend, depending on what’s grown locally. I sometimes wonder if the yemish originally had to include seven ingredients for luck?

We are fortunate to have relations with vineyards and orchards, my mother mixes various homegrown sultanas, raisins, currants, figs, apricots, with walnuts, pistachios, almonds, hazelnuts, etc. We also make mianpour dried nectarines or pears filled with sugar and ground almonds, apricot kernels or walnuts a real treat.

My mother always washes all the nuts and dried fruit before drying and mixing them. In our family, there’s also a charming tradition of throwing a few nuts into the corners of the room — a symbolic gesture for future prosperity and, perhaps, providing a small unexpected delight.

Then there’s soojough and baslugh. The best ones come from the city of Maragheh, famous for its vineyards (they grow the best grapes), its soap, and its historic observatory.

Soojough, found throughout the region, is made by threading nuts on a string and coating them in grape or pomegranate molasses. They look like edible garlands — or garvazah, as we say.

Baslugh is similar to Turkish delight. In fact, the Azeri equivalent of “once in a blue moon” is “Maraghah baslugidi”, since they are only made and available once a year!

Either on Akhir Charshanba or on the night before Nowruz, we eat rishta pilow, or “worm pilow,” as my sister and I used to call it, served with green joy khurushi or ghormeh sabzi (Iran’s national dish, apparently Azeri in origin).

Just as other cultures eat noodles at the New Year for symbolic reasons, there’s meaning in this dish too. In Iranian, reshteh means both noodles and threads. Perhaps these noodles represent the threads of family ties or even the reins of one’s destiny. And, about a hundred years ago, rice was rare and reserved for celebrations; stretching it with wheat noodles made the dish more plentiful for festive gatherings.

What are your family traditions and celebrations?

I’d love to hear — please share them in the comment box below.

Merci, and may good fortune and a rosy glow shine on our planet and all of us.