My social media feeds have been full of jokes, recipes, and ideas for how to make January or the “long, dark, cold month” pass more quickly. As soon as New Year is over, I check for the date and animal of the coming Chinese New Year and start planning our Burn’s Night meal. When these two dates have been close together, I have hosted a few Chinese Burn’s Nights, where we serve haggis, brought in to the sound of bagpipes and cut with a Samurai sword. We eat this with neeps and tatties and a shot of whisky as the first course, then switch our knives and forks for chopsticks and follow it with a variety of Chinese dishes and champagne. I love to make Ken Hom’s recipe for potstickers. I make at least 20 for myself and eat them in one sitting with a homemade sweet chilli dipping sauce.

Then I am on the look out for heart shaped things around Valentin’s day and next is my most significant annual event: Nowruz Bayrami (the spring equinox) or my Azeri New Year. Before I know it, it’s time to chit potatoes, start sowing seeds and pulling rhubarb. All this keeps me oblivious to the doom and gloom others associate with winter months. Maybe it is because I grew up with three calendars, one where the year starts in January, another new year in late march, and another which moves around the year?

Most of us mark the year by the change in the seasons, birthdays, and holidays. Gardeners have a few more dates in their calendar, with associated tasks, and those who cook also have recipes or preserves they make at particular times of the year when the ingredients are at their best.

I have been enchanted with the charmingly named Japanese micro-seasons, known as kō since reading about them in Mark Diacono’s Substack. It has become my conversation opener with anyone I have met since. I have even bookmarked this site and check regularly here.

In this Japanese tradition, the year is divided into 72 micro-seasons, with each kō lasting about five days. Such as “Fish swim after the thaw” which is in mid February. Though they do not correspond to the microclimate where I live, I can relate to the sentiment and natural phenomena they refer to.

What I like to call "selfish mindfulness" is all the rage these days, with people focusing exclusively on their own peace of mind. But how can you have peace when the world is burning around you? Yes, you must find peace within yourself first, but it should then emanate outward, the bit that is missing.

Maybe kō the shorter, more manageable periods relating to the ever-changing natural phenomena could help us achieve true mindfulness. By making us look around, become more aware of our environment, and notice all the beings in it, how light and the length of day or night affect the elements, plants, animals, and humans. Observing these subtle changes in our personal peace of mind, and at the same time, wishing for the same time, space, and freedom for others to enjoy them too. Then acting to make it happen.

Not kō, but observing what is happening around us. As I write this, six planets in our solar system are lining up, seemingly in a straight line and close to each other, all on one side of the Sun. For the last few months, on clear nights, four of them have been visible as large, bright stars in the sky. Saturn and Venus in the west were so bright that I had to do a double take, thinking they were plane lights. Jupiter and Mars, with its orange hue, have been visible in the east. Though the Moon is not a planet, at the same time, the waning crescent Moon has been low in the southern sky at dawn.

I have wondered if these celestial sights have been seen by those in conflict zones, and if, in that fleeting moment, they brought a glint of joy and wonder to their hearts.

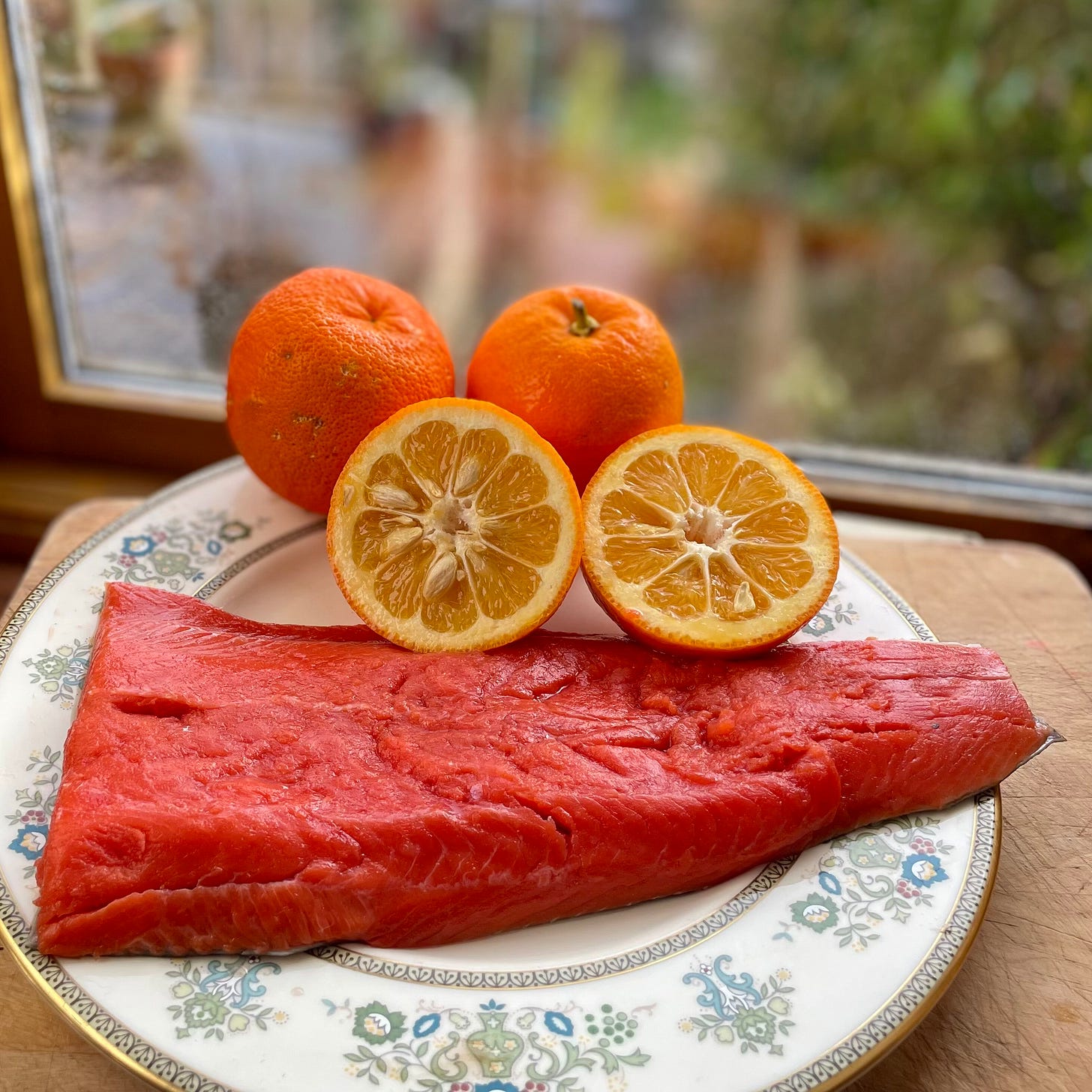

Back to narish as we call it in Azeri, this is the first fruit of year in the West. Just after New Year’s Day, I start looking out for narish, fragrant, knobby-skinned glowing orange orbs in the shops, and begin planning my marmalading. Known botanically as Citrus × aurantium and more commonly as sour, bitter, or Seville oranges. It is also called narenj in many languages, with slight variations in pronunciation across Eurasia. This is where we get the word “orange” for both the fruit and the colour. In Iran, there are many famous narenjestan (orangeries) especially in Shiraz. The word is ancient, originating in the lands that are modern-day Iran and India.

Interestingly, sweet oranges are called portagal in Azeri, Farsi, Turkish, and many other languages. It is said that the name comes from the Portuguese, who introduced these oranges during their voyages, using them to combat scurvy. The fruit became associated with them, and the name stuck.

Similar to many other things, this fruit was taken westward, and wherever it thrived, it became part of the local culture. The climate of southern Spain suited these trees perfectly, and they became integral to the city and palace gardens. Seville, or Ishbiliya as it was called during Arab rule, was known as the “bride of al-Andalus.” Its fertile soil supported miles of citrus trees, including lemons and narish, which were grown along the riversides and around the ponds in palace gardens.

I planned my journey along the Al Caliphate route in southern Spain to coincide with the orange blossom season. The heady scent of those white blooms in the Orange Tree Courtyard of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba and the Generalife of the Alhambra in Granada was sensational. In the Caspian region of Iran, where most of the country’s citrus is grown, the air in late spring is perfumed with orange blossom.

These beautiful evergreen trees offer shade in the summer, and their leaves, flowers, and fruit have countless uses in food, cosmetics, perfumes, and therapy. Young leaves can be made into tea. The flowers are distilled to produce orange blossom water. The petals are painstakingly separated, processed to remove their bitterness, and turned into fragrant jam. Oil is extracted from the flowers to make neroli, a key ingredient in perfumes and cosmetics.

Narish are not as juicy as other citrus fruit, but the little juice they have has a wonderful flavour. Their juice is squeezed into stews, on fish, chicken, salads and drinks to enhancing their taste. We know this sweet-and-sour taste as maykhosh in Azeri. When they are in season, in our family, it is the only sour element used in all cooking and food preparations. The juice will keep in the fridge for about a month and can be used instead of verjuice, lemon, or vinegar in cooking and dressings. In restaurants, they put the fruit in a gauze to catch the pips on the side of the plate for diners to squeeze onto their meal.

I like to squeeze it into the pan juices towards the end of frying fish in butter and olive oil. I have also read that the juice is boiled into thick brown narish molasses.

The skin of the fruit is dried and powdered for therapeutic purposes. Effat Khanum, whom I consulted for this piece, lived in the Caspian region and mentioned a tea made with powdered skin to calm the pain of her stomach ulcers. The extracts from this fruit are quite potent; therefore, they must be used sparingly. If you have underlying medical conditions, check to ensure it won’t interfere with those ailments or any medications.

These oranges are quite sour and their skin is bitter. In the UK we do not take out this bitterness as marmalade is suppose to have a bitter tang. In Iran when making this jam they de-bitter it before cooking, not only that, but also orange skin jam is presented quite differently too. First the peel the oranges carefully to have 4 pieces, the pith removed, then they are halved along the length, then they are rolled and secured by threading them on a string with a needle. Making a pretty long necklace of orange twirls. Then they are made into jam.

Another quality of these fruit are their thick pith and many seeds both full of pectin which help set this preserve. Essential to the marmalading process.

The word “marmalade” originates from honey (meli) and apple (mēlon) with roots in a variety of languages such as Proto Indo European/ Greek. Honey was and is still used as a sweet preservative in many countries. The word “marmalade” and the foodstuff arrived in the UK with those travelling Portuguese. Marmalade was a generic term for things cooked in sugar, not just orange peel. At the time, thier marmalade was made with quinces. Quince paste is now more commonly known as membrillo and is associated with Spain. In Azeri, our jams are called murraba. UK-style jams are known as marmalad in Azeri, where the fruit is mixed in with the sugar, loses some of its shape in the jam.

To get myself into the marmalading zone I start by watching Pam Corbin’s charming video on how to make marmalade. Then I glance through my recipe with highlighted warnings such as:

“Towards the end, when you are tired, don’t let it catch on the bottom,” BURNS QUICKLY, “Don’t rush or have any plans for the day you are making the marmalade” (underlined), and “Wear a long-sleeved top in case hot marmalade jumps out of the pan when you stir.”

Do not rush cooking any food, but especially preserving—particularly marmalade making—at any part of the process. Spread it out over two or three days and take the attitude that it’ll be ready when it’s ready. Yes, there have been accidents, and it has proven costly. One time, I was in a rush for it to set and took it off before it was ready. A day later, it was still swishing around in the jar, so I had to decant it, wash the jars, boil the jam again, sterilise the jars and lids, and do it all over again.

Another time, it caught at the bottom, and I had to carefully collect the unburnt top part into two other pans. Then, I washed the maslin pan and got it back on the heat.

There was also the time I used a pan that was too small, and it boiled over, leaving behind a lovely aroma of burnt marmalade.I had to continue the process in two pans. And then there was the time I hadn’t secured the pith bag properly, and it opened up. I had to fish it out of the hot syrup before it broke apart into the marmalade.

Don’t let any of this put you off, I’m sharing these experiences to let you know that things do go wrong, and if they do, there are ways to recover. This is why keeping notes is so important—I’ve never made the same mistake twice.

I find in the UK people like their jam well set unlike French or Azeri jams. The most common method for checking if your preserve is set is to use a thermometer (I have never succeeded with this technique). Instead, I use the put it on something cold, and see if it runs or sits in place. Traditionally a saucer is put in the freezer ready for this test; I use teaspoons. They take up less room and chill quickly. I also have another technique detailed below which isn’t safe but works for me.

I’m not sure why or how I’ve come to make such thick jams and marmalades. Considering where I come from where jamming is an art, and the fruit’s beauty is preserved by cooking it slowly in a thick syrup, rather than boiling it so hard that it disintegrates. Illustrated by the orange twirls in the photo above which are carefully taken off the sting and presented to the diners rather than spoon of marmalade in a lump. Azeri murraba are like jewels glistening in their clear syrup, whereas my jams and marmalades need to be spread with a knife. I suppose when our parents taught us “When in Rome…”. This just means I can make a variety of preserves, some more time consuming and prettier to look at than others but if I may say so myself, all of them keep well and are very good to eat.

Usually I make marmalade over two days, this year, I made it over three, and it worked out very well. This is a good way to do it especially if you’re using more than 2kg of fruit.

To start the process, make sure you have enough sugar, jars, lids, and lemons. Get your equipment, you’ll need a measuring jug or scales (to measure juice or water), a lemon juicer, a clean, tightly woven (ideally unbleached) cotton cloth or bag to collect the pith, and a jam funnel (you can ask around and borrow one). A maslin pan is ideal because it has a wide bottom and high sides, but any roomy pan that isn’t coated or reactive will do. Make sure the pan as big as possible to contain the fruit, liquid and there is room for it boil and come up the sides.

On mum’s last visit to the UK, she sewed me a marmalade pith bag and another bag for straining dairy to make suzma or cheese. These practical gifts are among my most treasured kitchenalia, and they make me smile with gratitude every time I use them.

You’ll also need a good heat source, especially if you’re making large quantities to get a rolling boil. I’ve had trouble using a large pan on a weak heat source—it didn’t get hot enough, and I had to split the jam into smaller pans and bring each to the boil. So far, it may sound like my jam and marmalade-making is chaotic and messy, but in 14 years of making jams—and especially when I used to make 15kg of each fruit—there have only been a handful of sticky disasters.

All citrus ripen on the tree; they don’t ripen much after being picked, so make sure your oranges look good and smell nice. You can freeze a kilo of fruit if you want to make more marmalade later in the year. To use frozen fruit, defrost and treat it as detailed below. I only use organic narish (bitter, sour, or Seville oranges).

There are recipes that involve boiling the whole fruit and then slivering it. I haven’t tried that method. I cut the fruit first, then make the marmalade.

You can also make citrus jam with other fruit or mixed citrus peels. I’ve made a four peel jam using sweet oranges, lemons, bergamot, and grapefruit. You can add flavourings into the jars before adding the hot marmalade, such as whisky, rum, or dry, freshly grated ginger or orange blossom water. Overall, though, I prefer mine au naturel. I only experiment with different sugars to create variations in flavour and colour, for example bleached white sugar, light brown sugar, or dark brown sugar each contribute different levels of caramel notes to the marmalade.

This recipe is adapted from Pam Corbin’s recipes, which you can find in her books: Preserves: River Cottage Handbook No. 2 (2008) & Pam the Jam: The Book of Preserves (2019)

Thank you, Pam, for sharing your passion for preserving and your gentle guidance.

As mentioned previously you can make marmalade with this method over two or three days.

Ingredients:

1 kg Organic Seville / Bitter / Sour oranges

1 tsp of natural salt with no chemicals

Depending on the juice that comes out of the oranges, top it up to make 2 ltrs of liquid total

1,350g of 50:50 Light brown sugar and white granulated sugar

The juice of 3 lemons

Day one:

On the first day, gather all the equipment and ingredients. Wash and take out the top hard bit known as the button of the narish. Juice them and collect the juice in a measuring jug or weigh it at the end. As you juice, collect any pips and pith and place them in a cloth or pith bag. Once the oranges are all juiced, then scrape the pith and add it to the bag. Tie the opening of the bag very securely.

Next, shred the peel to your preferred size. If you want fine shreds, make sure they’re consistently thin; for thicker shreds (my preference), aim for about 5 mm. Thicker peel will take longer to cook. Place the pith bag and shredded peel into a large pan with plenty of headroom for the liquid to boil up later. If your pan isn’t big enough, split the mixture between two pots. For every kilo of whole fruit, add two litres of water which includes the juice from the oranges. Add one teaspoon of pure that is, non-chemical salt, per kilo of oranges. Cover the pan and leave it overnight or for 24 hours in a cool place. In January, in the northern hemisphere when these fruit are in season, you can leave it on the counter unless your home is particularly warm.

Day two:

The next day, place the pan on the heat and bring it to a boil, then lower it to a simmer. Cook the peel with or without a lid; partially covering the pan helps bring it to a boil quicker on lower-power cookers. Thick peel usually takes about two hours to cook, so start checking after an hour and a half. To test, take a piece of the thickest peel you can find and squeeze it between your fingers, if it’s soft and mushy, it’s done; if there is any give, cook it for another half an hour.

Turn the heat down and add 1,350 grams of sugar per kilo of fruit. I like to use a 50:50 mix of soft light brown sugar and white sugar. Stir until all the sugar has dissolved—there should be no grains before you boil.

At this point, you can either leave it overnight and finish the marmalade the next day or proceed to the next step. Sterilise your jars when you start this process.

Boil the lids for five minutes, then place them on a clean surface without touching the inside. Put the jars in an 180°C (fan oven) for 10 minutes, then switch the oven off and leave them there until needed. Pour boiling water over your utensils which are going to come into contact with the jam, that is, plate, spoon, ladle, jam funnel, and spatula—and let them air dry.

Take out the pith bag and squeeze as much sticky liquor as possible back into the pan. This may make the marmalade slightly cloudy, but it’s full of pectin to help it set. Discard the pith.

Juice the lemons, using two per kilo of oranges (or three if they’re not very juicy), and add the lemon juice to the pan. Stir to combine.

Put the pan back on the heat and bring it to a boil. Let it boil for about twenty minutes, stirring regularly to prevent it from catching at the bottom. Be cautious—marmalade boils up, splutters, and can burn! Wear a long-sleeved top and use a long-handled wooden spoon or spatula. Watch the froth on top and notice how the bubbles change. They’ll go from small and pale to larger and slightly darker, with a distinct crackling sound it is starting to come to setting point. From this point on every 3 minutes or so I stir the marmalade and if it spits back with rage then I turn off the heat as I know it is ready. I tend to stir it until the bubbles dissipate then skim off any solidified foam from the edges and let the marmalade cool for about fifteen minutes. When you do this the peel will distribute evenly in the jelly rather than all float to the top.

Use a jam funnel or ladle to pour the marmalade into jars, leaving about 5 mm of headspace. Hold the hot jars with a cloth and screw the lids on firmly. Wait for the joyous “plinking” sound as the marmalade cools and seals the lids. Wash off any stickiness and label the jars once dry.

You can enjoy marmalade with scones, croissants and on toast. I once made Jamie Oliver’s speedy sponge pudding, which was as delicious as it was dangerous. It is so easy and quick to make, one could eat it more regularly than one should.

In savoury dishes, I’ve used it in a carrot and rice dish known as yechoci pilow and as a finishing sauce on chicken thighs. Here I mix the marmalade with grain mustard and garlic, and pour it on top of the chickne in the last 5 minutes of cooking.

Today kō is: “Ice thickens on streams” until the 29th of January. Not where I am, it is blowing a gale and raining, the forecast is 8°C / 46°F! You still have time till mid February, or “Rain moistens the soil”, to make marmalade.

BTW it was Burn’s Night last night and Chinese New Year of the Wood Snake starts from the 29th of January.

I apologize for this tardy newsletter. I was finishing my manuscript for The Fermented Dairy of Central Asia, and it took a bit longer than I had expected. It is with the publishers now.

Loved this substack. I've (tried) to make marmalade several times-never perfect. I'll follow your recipe (failures and all) again.

I look forward to your book on fermented foods. Please keep me posted!

Shahina