Sheep are not just for counting (to put you to sleep); they are also a source of food, drink, clothing, musical instruments, paper, toys and much more. In this newsletter, I’ll share some of my sheep knowledge and a recipe for govurma a meat preservation technique.

Sheep are relatively docile1 and gregarious animals which flock and are inclined to follow a leader - part of the reason why 11,000 years ago our ancestors herded them. Initially sheep were kept so that our forebears didn’t have to go far to get meat. Later, we started using them for all sorts of purposes, dead and alive. British archeologist Andrew Sherratt, in his controversial theory, suggested in the initial phase of our keeping animals sheep would have been deadstock, saying we would eat or use their bones, wool, skin only after they had died. His “secondary products revolution” is when our ancestors realised they could use their flocks as livestock, giving them a continuous supply of say milk and wool.

Nowadays, there are many breeds of sheep, they are said to have a common ancestor in mouflon (Ovis gmelini) native to Azerbaijan. Fat-tailed sheep or goyun are the most common in Azerbaijan . Coincidently, like me, fat-tailed sheep were introduced to Anglesey in more recent times. These sheep can survive harsh environments, like the hills of North Wales and their meat is nutritious, more flavoursome, tender and juicy than their thin-tailed cousins.

Modern commercially driven breeding programs of all herd animals are focused on creating animals with all the characteristics we want for meat, milk, wool and the right temperament, not necessarily focusing on our nutrition or the wellbeing of the animal and environment. The most famous sheep is Dolly, the first mammal to be cloned. Sheep and goats are closely related and I thought it cute that the offspring of a ewe and male goat buck is a geep (one for the scrabble players).

15,000 years ago or so, grey wolves started to come to our ancestors in search of food scraps, eventually staying as they offered protection. These natural predators were later trained to help us hunt as well. Staying with dogs and Wales for a moment longer, my parents were fascinated by clever sheepdogs on the farms near our home in Wales. At the time there was a TV show they’d never miss called “One Man And His Dog” showing sheepdog trials. In other parts of the world, donkeys and llamas are used as guard animals too. “One Man And His Llama”: now that’s a show I’d like to see.

Herding sheep transformed the way humans lived. Prior to this, some were nomads and others settled. Once we started keeping animals however, we had to cater to their needs as well. Those living in areas with enough pasture throughout the year remained settled. Those who didn’t had to move to greener pastures. This was either done by wholesale move of all the tribe and the flock usually seasonally and to a higher elevation in the summer and is known as pastoral nomadism. I had the great pleasure of meeting two of the largest pastoral nomadic groups of modern times, the Shahsuvan in Azerbaijan and the Gashgai in Shiraz. The other way to keep a flock is transhumance, where some of the tribe take the sheep to pasture on a seasonal basis, whilst the rest stay back at base. Most western depictions of shepherds in art are usually a boy or man and flock in a bucolic setting.

So intrinsic were sheep to the life of those who keep them, they entered the language and culture. From the time we started making up stories and writing them down, shepherds and sheep feature heavily. The earliest example so far is from the Epic of Gilgamesh written over 4000 years ago, Enkidu a commander and friend of Gilgamesh is said to have been 'civilised' after spending time with shepherds. Later, shepherds feature in Greek and Roman mythology: Apollo, Pan and others all spent time looking after sheep or finding babies and bringing them up. I’m thinking of Romulus and Remus who were suckled by a she-wolf but brought up by the shepherd Faustulus. Jason found the Golden Fleece in the Caucuses; it was golden because, according to some, fleece was used to trap gold fragments from streams. In the 12thcentury poem by Nizami a Ganjavi, Layli o Majnun which is based on earlier Arabic stories about ill-fated lovers, Majnun visits Layli disguised as a sheep depicted in the miniature below.

In more modern times sheep appear in fables and nursery rhymes, such as Baa Baa Black Sheep2, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, and then there wolves dressed up as sheep and grandmothers. There are many sayings in English: “counting sheep” to go to sleep, believed to have originated with shepherds who wouldn’t sleep until they had accounted for all their charges; the idiom, “black sheep”; the adjective: sheepish; portmanteau neologism, sheeple or goyunchimin in Azeri; and the derogatory: mutton dressed as lamb. Bristol based, Aardman Animations make charming stop-motion animated films. Shaun, a sheep, features in two of their films; The adventures of Shaun the Sheep and A Close Shave.

For many peoples throughout the ages, the shepherd or choban has been a powerful figure and metaphor. They guided and cared for what would have been a valuable possession, the flock. Characteristics such as vigilance, caring and wisdom would have been associated with them. A local friend Grace is a shepherdess or khanum choban (I’m guessing). She has a lovely shepherd’s hut and keeps Cotswold Lion sheep introduced to the area by Romans. They are even mentioned in the Doomsday Book of 1068.

I have also read that it was the weakest in the tribe who would keep an eye on the sheep because it wasn’t a difficult job. If that were the case, sheep could have been cared for by the young, old and both sexes. Despite the remains of “Elba the Shepherdess” who lived over 9000 years, there aren’t many references to girls or women looking after the sheep though it must have happened, we just have Little Bo Peep, who lost her sheep!

On a visit to one of the villages in the mountains of Azerbaijan, we arrived at what could be called sheep rush hour; it was when the shepherds were returning from the hills to return sheep to their owners. The narrow alleys were filled with sheep and house doors were left open, every now and then a few sheep went inside. It was so full of life, frenetic, smelly and noisy. I didn’t get a chance to ask them how it worked exactly but it seemed each sheep went into their own home. There might have been a few errors but I guess it’d resolve itself another day. Apparently cows and donkeys are homing too.

Sheep feature in status symbols and identity. Sheep, lambs and goats are on many coats of arms, they symbolise gentleness, innocence, purity and sacrifice. Not only flock size but also flock colour mattered too, so much so that tribes were distinguished by the colour of their sheep. Between the 14th and16th centuries there were battles between rival Turkmen tribes for control of lands from Anatolia to Azerbaijan. The Gara Goyunli tribe (those with black sheep) and those with white sheep, Agh Goyunli.

From ancient times sheep have been represented in belief systems, for example the Egyptian's Khnum, the ram god who was associated with the Nile, fertility and creation. Then there is the constellation of Aries, and in the Abrahamic faiths, sheep and shepherds have prominence. In the text and as part of rituals. “The lord is my shepherd”3 from the bible or Eid ul-Adha ('Festival of Sacrifice') and Gurban Bayrami in Azeri an important festival for Muslims. This festival is a reminder of the prophet Ibrahim's willingness to sacrifice his son when God ordered him to. Spoiler alert, a sheep was sacrificed instead. This festival is also known as Haji bayrami. Part of the extensive rituals for returning pilgrims from the Hajj is to sacrifice and give two thirds of the slaughtered meat as votive gifts to their communities. It is portioned and distributed cooked or raw.

Here I have to share with you the first time I ever had fresh spring milk from sheep kept in the Liqvan hills of Azerbaijan. We were visiting friends at their bogh (forest garden) and their gardener Mohabat, brought milk as a gift from his village. The sheep of this village are grazed on the slopes of Sahand mountain and the cheese made from this milk is the best in Iran. Panir is the general term for cheese but Liqvan paniri is the crème de la crème. It is like what is known as feta cheese in the west. Our hostess Soraya Khanum pasteurised the milk in a large pot then brought it to us as elevenses. I’m not a milk drinker so I initially declined, but when I heard the oooo ahhh of the others, I had some, wow! It was revelatory. The first thing I noticed was how sweet it was and I asked if they’d added sugar but they hadn’t. The warmth and fattiness of the milk allowed all the aromas and flavours to be released and it was a multilayered taste sensation. It’s of my all time most memorable drinks and a privilege to taste the place and past in the little glass of warm milk 9 years ago.

Sheep wanted dead or alive

When sheep are alive, we get wool, milk, blood and lanolin. After the animal is slaughtered, not only do we eat them but we also use them for giving us light, cosmetics, waterproofing, heat, fabric, musical instruments, containers, paper, tools, objet d'art, toys and much more. Their fat can be used to make candles, makeup, lubrication, soap and waterproofing; their wool to make fabrics, their intestines as sausage casing or catgut, a type of twine used in many ways including strings of a musical instrument. Their stomach may be used as a container, which if put in a lamb’s stomach turns dairy into cheese. Their droppings high in cellulose used for paper making and fertiliser and their bones carved into art, tools and toys to name a few.

There are many games played with bones around the world, I remember my father telling us how he played ashikh with his friends as a child. Ashigh are the knucklebones of sheep, cows, camels, wolves or other animals. In Azerbaijan it is usually sheep or goat knucklebones and they are used like marbles or dice. They are also used as tokens of friendship, musical instruments and for telling fortunes. In Mongolia they are known as shagai and are listed as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. Dominoes were originally made of bones and are sometimes known as a game of bones.

The round bone in the photo above are known as jalin boghan in Azeri or bride choker, it is the femoral head and has slippery coating. The story goes, a bride was enjoying some meat on her wedding day and sucked on this bone and it slipped and suffocated her. Not just a noun but a vivid hazard warning.

In English a live, young sheep of either sex is called a lamb, an adult female a ewe, an intact male a ram and a castrated male a wether. These names have associated characteristics, for example, sport teams are called rams. I found one use of the female form: Derby County FC’s women’s team is called Ewe Rams. Lambs as previously mentioned are considered innocent and cute. Growing up in Wales the prancing spring lambs amongst the daffodils was a delight to look forward to in the springtime. Meat of either sex, if less than a year old is called lamb; of either sex between 1 – 2 years old hogget; and if older than 2 years - the meat of a ewe or wether - is called mutton.

Marks on bone remains tell us that we humans have been eating meat that we either hunted, scrounged or scavenged for over 2.4 million years. We would have eaten anything that moved. In a recent Netflix documentary “Secrets of the Neanderthals’ they showed how Neanderthals buried the bones of their dead with posies and marked where the grave was. Some of the 70,000 year old human bones found had butchery marks on them indicating cannibalism.

We would have started eating meat raw, then maybe if we were in a region with natural fire such as forest fires, lightning strikes or natural gas in the ground igniting we would have scavenged and eaten “cooked” meat. This omnivorous behaviour led to our species’ brain growth and therefore have the capacity to harness fire, a uniquely human trait. Cooking made the food easier to digest and eat. Simultaneously we were improving our stone tools, containers and communication skills. These cumulative changes to our body, brain and behaviour allowed us to be more efficient and develop skills which we then shared with our kin. Butchery skills we developed would have meant we were able to extract and process the raw meat to make it easier to eat, and cooking killed the pathogens making it safer to eat.

From the 13th century there has been a butcher’s guild in the UK, specialist in slaughtering, dressing and selling animals. I’m very happy to see a resurgence of nose-to-tail or respecting the whole animal rather than just eating particular cuts of meat. In Azerbaijan, they don’t hang meat to age, rather most of the meat is eaten fresh. This is particularly the case for offal. I remember whenever we sacrificed sheep the first thing to eat was liver kabab. Thin strips of liver threaded on small flat skewers, held for a minute or so over the coals and sprinkled with salt. When my sister and I visit mum, it is a treat we go out to enjoy at little kiosks which just sell offal kabab.

Depending on environmental conditions and available technology we would eat or preserve the meat. In cold places meat would be frozen and in the arid Steppe of Central Asia dried. /For example, borts are a Mongolian essential, they are dried thin strips of meat, eaten like jerky, or powdered into a soup. Other methods of preserving meat is to cure with salt, encase it in a skin with lots of spices and herbs into a sausage or keep it in oil, an Azeri speciality govurma (recipe below).

Up to mass use of electricity and fridges, butchers’ shops closed in late spring in Azerbaijan because it was too hot to safely store meat. They would have a summer job or be called upon for sacrifice duties if religious high days and holidays were to fall over the summer time.

Lamb butchery at The Newt

The word newt in Azeri is more of a description than a noun, suda-quruda yaşayan quyruqlilar which translates to in-the- water-and -in-the-dry-living-tailed-things. I set off on a beautiful misty morning which happened to be Diwali and Halloween to attend a butchery course at The Newt (I paid for myself). I arrived in glorious sunshine and after a brief wander around the grounds, a coffee and cinnamon bun we were taken to what we were told was the best butchery building in the world. On the way we stopped to see how the cows were kept in a massive open-sided pens with a large wooden round roof. There was a bridge and platform over the pen so you could observe cattle below. The spoke-like sections of the pen allow for separating cattle or feeding them in the most efficient and least disturbing manner.

Then onto the butchery building which you see in the photos below, it had a modern cathedral cum butchery vibe. You enter the structure through a curved glass entrance under a large cantilevered second floor. Inside it had very high ceilings with light wells allowing natural light to beam into the quiet almost hallowed space. Walking through the corridor we were flanked either side with glass rooms for various meat products. The facility as a whole and each room is temperature and humidity controlled with heated glazing to prevent condensation. There was a large room for making various meat products such as charcuterie, sausages, burgers and a smoke room all connected at the back via corridors to the various areas described above. This room looked out to the area we were going to work in. There as in the shop butchery, another beautiful Himalayan salt room for aging meat which looked like a jewellery box. I love beautiful things which are also practical and designed with consideration and care. In this butchery one see what can be achieved with a lot of money, and where beautiful form and great function meat. See what I did there?

Lloyd was our teacher, and has been the butcher there right from the beginning. This was his last class, after which he’ll be leaving to tend to his family farming business. He started the class by cutting a whole lamb into four manageable pieces, then he showed us how to prepare some pieces.

First we started by trimming the lamb skirt - the bit under the belly. I chose to keep mine whole, the others rolled it around minced lamb which we’d been given.

Then the group deboned the whole shoulder of lamb, which they stuffed with the remaining merguez. I halved my shoulder to keep one part for roasting and the other part I deboned and diced into pieces for the recipe below. I’d asked for lamb fat for rendering, Lloyd suggested I take the suet which is the fat in the cavity of the animal near the organs. It had a different look and feel to the rest of the fat on the body of the meat, it was very crumbly (I’ll come to this later). Before attending the class I’d read it was best to mince the fat before rendering so whilst the others deboned their shoulder I diced the suet. Finally, we French trimmed cutlets. Needless to say we all came away with lots of bags of goodies to cook, freeze or share.

We had lunch in one of the many restaurants on site, it was another beautiful room. We had seasonal vegetables from the estate and of course, lamb. After lunch, I decided to walk back to see how the place had changed since my last visit 5 years ago when they’d just opened. When I visited then it was quite small and just as far as the decorative vegetable patch which had been laid out but not planted. I’d say the place had grown by 20 times or more. On the way I saw a large branch and twig Gruffalo ready for their staff fire night next week. I came away reminded how much we are affected by fruit, vegetable and meat grown with care in a beautiful surroundings.

This summer the Oxford Food Symposium theme was Gardens, Flowers and Fruit. I’d written a paper about the Pleasures of Persian Gardens and in it explained how 1000s of years ago when people entered either royal gardens or city states, from the outside barren arid landscape through the garden doors they’d be in awe of the symmetry, order, life and beauty within these spaces. It is still the same, to be in a safe, ordered garden conjures the same feelings now as it must have done then.

When I got home I decided to freeze some of my meat, eat the rack with a pistachio and herb crust and then render the fat and poach the diced shoulder to make govurma. This is the Turkic word for slow, low temperature fried food. The word has travelled far and wide and is pronounced differently. It has been adapted to a variety of cuisines. Such as Persian braised dishes like ghormeh, or you may think it sounds similar to korma on an Indian menu. You’d be right, they share the same origin and name and are from the humble recipe below. To Govurmakh (the verb), to fry slowly and gently, gizarmakh is to go red or golden and is to caramelise.

In times past, meat was a luxury. When the animal was ready for the pot it was all eaten, nothing was wasted. The best cuts were usually enjoyed as part of the celebratory meal and the rest would have been added to other dishes to make meals. The fat and stock were used to add flavour and body to everyday dishes. In last month’s newsletter, I suggested adding stock to the alma shilasi to give it umami. My most favourite bit of mutton is the leg bone marrow, I even have a silver marrow scoop.

The blood is also used in many cultures but in Azerbaijan where the majority are muslim it is forbidden to eat blood so it isn’t used. Whilst I’m on the subject of religious dietary rules how an animal is slaughtered is also important, for example the Islamic dhabihah method of slaughter gives us halal meat and the Jewish shechita makes it kosher.

There are many different sheep meat dishes, depending on the type of meat as well as the fat to meat ratio of the cut, each needs to be cooked differently. Muscle meat can be cubed and slow cooked in stews and braises, or cut in very particular way, beaten, marinated then threaded onto skewers called shishlikh or kabob, minced for geema, rissoles and chufta (meatballs) to name a few.

I can’t talk about mutton and not mention the famous Azeri breakfast of challa pacha, or poached sheep’s head and trotters, a classic example of eating every bit of the animal. I don’t mind the cheek and tongue but I’m not so keen on the texture of brain. The poaching liquor or ishchana is full of goodness, in fact trotter stock is called zinc. In the photos below you can see a street vendor preparing a head of a sheep, a barrow of trotters and one of the most famous challa pacha cafes in Tabriz, Ramsar.

We would have initially used animal fat for cooking, then when we started dairying, we made butter and ghee, eventually extracting oil from fruits and seeds such as olives or flax. In the modern world we have different types of oils to cook with, most highly processed and detrimental to our health. It turns out that animal fat is the best oil to use when frying at higher temperatures. Used in moderation this fat is healthier for us than some other oils. It has fat soluble vitamins A D E and K, fat-tailed sheep tallow is rich in omega 3, 6 and 9 fatty acids as well. This fat is shelf stable but as with most oils it’ll go rancid with exposure to heat and light. Kept in a fridge it could last for years. Different animal fat has a different taste, feel and colour. These fats tend to solidify at room temperature and therefore if the food is eaten cold they give a particular mouthfeel.

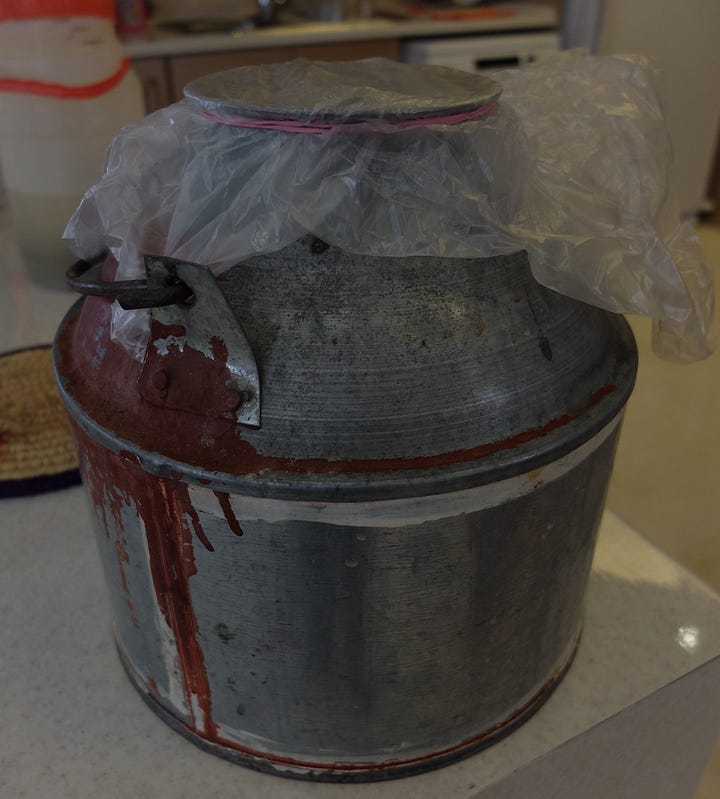

In the west most people are familiar with the term confit (to preserve), particularly duck legs. It is a preserving method applicable to many types of food, here I’ll share an old fashioned pre refrigeration technique for storing meat in oil called govurma. Once cooked the sterile food is then packed into containers and completely submerged in fat to create an anaerobic environment. Nomads would use light skins full of animal fat to preserve meat on the go, whilst settled people clay pots whilst settled people clay pots called govurma chupi and stored in a cool place.

Govurma making is slow and low heat cooking in fat, it isn’t like deep frying which is on high heat, quick and creates a crispy coat and moist inside. This technique takes hours during which time the connective tissue breaks down but because there isn’t too much evaporation the meat retains its moisture. It is done by cooking at around 70°C / 158°F which is when collagen begins to dissolve. Cooking in fat gives the meat flavour and keeps it tender by regulating the temperature and creating an inhospitable atmosphere for bacterial growth. This is a great technique for cooking tougher cuts from older animals such as mutton which is the most popular meat in Azerbaijan.

Whilst writing this, I also wondered if this method of cooking came about in Azerbaijan because people were at high elevations, Tabriz is at 1,300 m above sea level and as we know water boils at a lower temperature therefore food takes longer to cook? It’s just an idea, I’d be interested to know your thoughts especially if you live at high altitude.

Using pressure cookers is popular in Tabriz, it is both quicker (a blessing in the hot summer) and uses less energy. In the past they made natural pressure cookers. An intact - that is without any holes - stomach of an animal would be used as the container into which they’d put let’s say meat, some salt, a little water and hot rocks4. They’d tightly tie the stomach and as the water turned into steam the stomach would start to blow up, achieving higher temperature inside the skin and this cooked the food more quickly.

There are a couple of ways to make govurma, for me it is a three step process if you already have tallow. First you poach the meat, next you fry it in tallow very slowly and on a low heat for as long as it takes for it to be ready, then you cover it in fat and store it. As most of us don’t have tallow, I’ll also show how I made tallow from jan yoghi body fat. We don’t cook with suet, instead we use it topically or to waterproof plugs in garden ponds.

The other method is all-in-one where you dice the meat into walnut size pieces and chop the fat finely, then you put them both with a couple of whole onions and water to cover in a pan with a lid. Once it comes to the boil, turn it down to a low simmer and leave it for 4 to 5 hours for the fat to render and the lamb to poach. After a couple of hours there shouldn’t be too much liquid in the pan, at this stage you can take the onion out so you can start stirring it. To me this style is similar to the bhuna process in Indian cooking.

The resulting govurma is preserved cooked meat. It can be stored in a cool dark place or fridge for months. To use it, it is reheated and it can be eaten with bread/ rice/ potatoes and pickles to cut through the fat. It can also be used in more elaborate braises with vegetables and pulses or cooked with spicy creamy sauces.

Govurma stage one- Poaching the lamb

Ingredients

1kg lamb shoulder cubed onto golf ball size

50 ml of water

½ tsp salt

1 tsp peppercorns

140g of onion – either dropped in whole or if cut such that it doesn’t disintegrate and can be retrieved after the poaching

I usually poach meat in a tight fitting pot with a good seal to keep in all the cooking liquor. In this case I used a staub pot.

Method

Put all the ingredients in the pot, put the lid on and put it on a high heat to come to the boil. Once it starts to boil, turn it down to a poach and skim off any scum that rises to the top. Leave it for 30 minutes then start checking to see if the lamb is cooked but not too tender. We will be cooking it again in oil. The timing will depend on the age of the animal, cut of meat and the size you have cut the meat. You will have to check regularly to make sure it hasn’t dried out and if it has cooked. If it needs more water add it sparingly and then check every 10 minutes until it’s done.

When cooked, separate the stock and meat, make sure to take out all the onion. The cooked meat is called nijar and the stock ishchana. Ishchana is usually eaten with torn up pieces of bread which soak into it as a starter with sharp crisp raw onion. You can also use the stock in other dishes such as soups, risotto and sauces. When cool the fat rises to the top of the ishchana you can collect it and use this as cooking fat as well.

Lamb fat - tallow

There are different types of fat, jan yoghi is body fat and pee or suet. We only use jan yoghi for cooking, not suet.

Ingredients

For the kilo of poached lam you’ll need at least 740g of body fat, trimmings from around the shoulder and breast – chopped finely or minced.

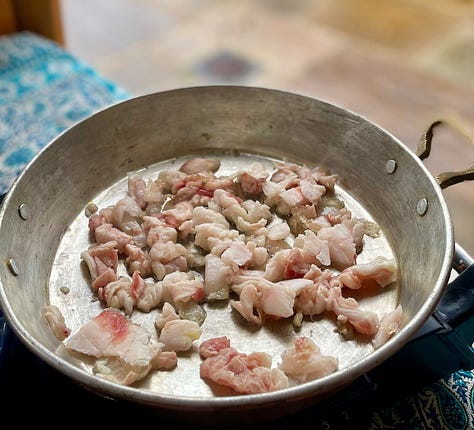

Method

Put the fat in a wide frying pan and put the heat on high, when you hear it just starting to sizzle, turn down the heat to low and let it melt slowly for an hour or more. This will depend on the size of the fat in the pan. You’ll start with a pan full of solid fat and end up with a pan of oil with little bits in it. You can keep going until the little bits are golden. The sieve it through a cloth and you have tallow.

The crispy bits can be fried further and eaten as a snack or used as sprinkles on savoury dishes.

Tallow solidify as it cools, keep it in a cool dark place or fridge and use as you would any oil.

If you don’t have much or intend to use it quickly, you can flavour the tallow with herbs and spices by adding them once it has started to melt in the pan. Keep flavoured tallow in the fridge.

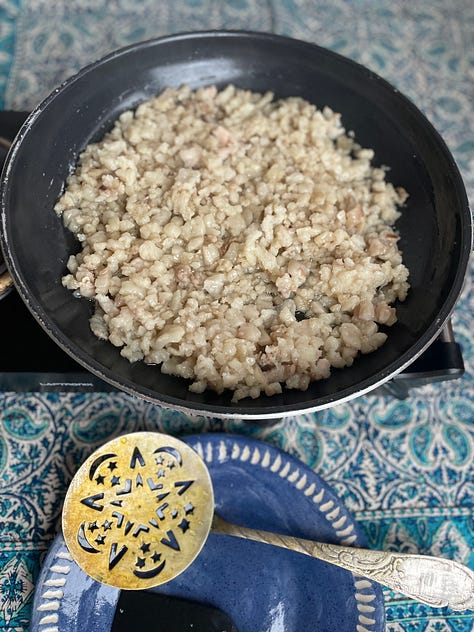

Govurma stage two

Ingredients

10 tbsp or more of tallow from above

Poached lamb from above

Method

Add the tallow and meat to a pan and heat it up, make sure you add enough fat to come up the side of the meat, it doesn’t need to be submerged but at least half way. As soon as you see bubbles forming, turn the heat down until there are small bubbles in the oil and round the meat like poaching around 70°C / 158°F. Check periodically and if it is colouring underneath, flip it over carefully. It is ready when the meat is caramelised lightly on the outside and this will depend on the size of the meat and quantity you are cooking. It will take anywhere from an hour to 1.5 to 3 hours. I only had a small amount, it was ready in an hour.

Then put the meat into a sterilised heat safe jar, pour the fat on top and if it isn’t fully submerged add more. Make sure there are no air holes in the container by tapping or shaking the container gently. Once cool the fat will solidify and become opaque then you can store it in a cool dark place or fridge to use as you need it.

I kept mine for a few days then ate it simply with fried onions and pickle.

To eat it, I heated jar of govurma gently in a pan of water, when the fat melts and is liquid I take the meat out and set it to one side. I used two tablespoons of fat to fry the onions. I fried the onions and added the meat to heat up with the onions in the last 10 minutes of cooking. The smell and the colour was irresistible. I ate it on sourdough toast with homemade onion and green tomato pickle. Though simple and a small portion it was satiating and satisfying. I kept the remaining tallow in the fridge and I’ll be cooking with it in the next couple of days. I mix it with olive oil as you would butter.

Except when ewes have lambs or when rams are in rut.

Baa Baa Black Sheep from Tommy Thumb's Pretty Song Book of about 1744.

Psalm 23, Ezekiel 34

Hot rock cooking was practiced all over the world, it is where rocks are put into the fire to heat up then used usually to boil liquids. I remember when I was in Canada at a Maple syrup farm they told us hot rocks were used to heat and reduce the sap into syrup.

Very illuminating, Simi - thanks for posting! The slow-cooked method you describe for preserving mutton in fat is also, as I'm sure you know, used in Andalucia to preserve pork and in the Languedoc to preserve goose.