Sesame seeds make me smile wistfully, reminding me of the delight in getting double-sided, seeded sanjayh (trying saying that twice in a row) and pretty little tins of halva. Chunjut, as they are known in Azeri, are a versatile, calcium packed ingredient in pip and paste form. I hope you enjoy the simple halva recipe below. With the holiday season upon us, why not make it as a gift to share?

Sesame seeds have been sprinkled on dough for millennia. The pharaohs were partial to it. My earliest experience of sesame is on sweet or savoury bakes in Azerbaijan. We buy fresh bread from a baker for each meal. Yes, you heard right, on most days we get dressed go to the baker, stand in a queue, and bring the bread home warm out of the oven, at least twice, if not three times a day. The type of bread we buy depends on the meal. Bakers open just before breakfast, lunch and dinner. You can stand in the single loaf or multiple loaves queue. Bread is very important and respected, we don’t throw it in the general waste bin and if we see it on the ground in the street, we put it to the side so it isn’t stepped on.

Sanjayh is the Azeri pronunciation of sangak bread, a Farsi word meaning pebbles, which gives the bread its name. Sanjayh is a wholewheat, slowly fermented sourdough bread made by shatir (expert), the name of sanjayh bakers. These bakeries have high ceilings as the bakers use very long handled peels, the wet dough is about 40 cm x 40cm on the peel, then the shatir pours it onto the pebbles spread on the base of tandir or oven. When the sanjayh comes out of the oven, it is over a metre long! We carefully pick off the hot pebbles on a wire rack in the bakery, before folding the bread into a large tea towel or draping it over your arm to take it home. You can have sanjayh with sesame seeds on one side, or both sides. At the baker’s, if someone asks the shatir for two sided, people in the bakery know it’s for a special occasion and acknowledge it with a smile. On one of my visits to Tabriz, my father’s friend knocked on our door at 7.30am with an arrival gift of ichi tarafli sanjayh or two sided sanjayh. There was such glee in the two men’s eyes in giving and receiving this special treat. That feeling has stayed with me.

I’m sorry to report, now not all, but most bread in Iran is awful. Bakers do the best they can with the available white powder labelled flour.

The English word sesame has it’s roots in a descriptive, Akkadian compound word samassammu which translates to oil plant, indicating its original use. As for where it originated, though the Latin name is Sesamum indicum (Indian), we are not actually sure if it originated, in Africa or India. What we do know is, it was grown over 5000 years ago in what is now Pakistan. The plant has beautiful flowers which become pods that look like okra. These pods, the leaves, and of course, the seeds are all edible. The pods crack open to release the seeds, a cracking sound similar to unlocking or the releasing of things within which may have been the inspiration for “Open Sesame”1.

Through trade, sesame plants were grown in many areas in the region. The oil was used as part of the mummification process in Egypt and it became an important crop in Mesopotamia2. 3000 year old administrative, cuneiform tablets document receipt of sesame oil, and Herodotus reports in his Histories that Babylonians “use no oil except what they make from sesame”3. Alongside other oils, sesame oil was used in oil lamps as well, and the resulting soot was used as ink.

These little seeds had many applications then, including therapeutic, cosmetic and even mystical: cakes were made which were burned to break spells cast by witches. Sesame oil can cause stomach upsets when ingested from which we get the charming Mesopotamian proverb: “farting like someone who has eaten sesame oil”4. Nowadays besides culinary purposes sesame oil is used in medicine and cosmetics, in this case casting good spells to rid us of wrinkles! I told you they were versatile.

Ground up sesame seeds are known as tahini. Tahini comes in slightly different flavours, colours and textures depending on the variety of seed, and whether it is hulled and toasted or not. The most common type found in jars in grocery stores is made with hulled, white seeds and have a mild flavour. How things are ground is important, it seems that small batch traditional techniques yield a fresh, flavoursome and more nutritious product. Of course, the soil and water are important too to produce healthier plants and food. Ethiopian Humera sesame seeds are said to be the best and are grow in good soil. The tahini from these seeds is rich and flavoursome.

Sesame seeds would have been stoneground in times past, with a consistency varying by method and miller. In contrast, today we like to “optimize production” by using high powered grinding machines, all sorts of filtration and chemical analyses to make consistent products. This sort of sterile consistency may be reliable but as mentioned previously, products are are not as tasty or nutritious.

Sesame are a source of fat, protein, vitamins and minerals, especially calcium. It is an allergen so do check if serving for a crowd. Generally speaking, the lighter tahini are made with hulled seeds and these usually taste milder than the darker ones which are made with ground whole seeds and tend to be more bitter. Far Eastern sesame pastes have a nuttier taste. Then there is black tahini, made from black sesame seeds. I use this one during halloween to make a spooky looking hummus bi tahini for parties, served with bright orange carrot crudités.

I manage to find a sesame fix wherever I am with universally available small packets of Sesame Snaps. When we were staying in Istanbul for a few months, every day I had a fresh Simit on the Eminonu side of the Bosporus and then go over the Galata bridge to have baghlava and chai on the Karakoy side in Gulluoglu. About three years ago, the Greek family run Basil Bakery opened in Bath and I found out they made sesame rings. It is my little treat; every now and then if I’m passing the area I’m passing the area I’ll pop in and get a koulouria. Often, I can’t wait to get home to eat it so I scarf it in the car. Needless to say there is evidence of these drive-by snacks in the car for days.

I always have white and black seeds and tahini in the kitchen. I sprinkle seeds on sweet and savoury dishes, bakes and especially far eastern recipes. I eat it spread on bread with honey, jam or syrup, as a dressing in salads, and make an array of dips and sides. I use tahini as a flavoursome non-stick coating on the inside of baking tins. Sesame is enjoyed all over the world, on baked goods, hummus bi tahini, baba ganoj, tahinosoupa, benne soup, recent versions of dandan noodles, and Japanese salts to name a few.

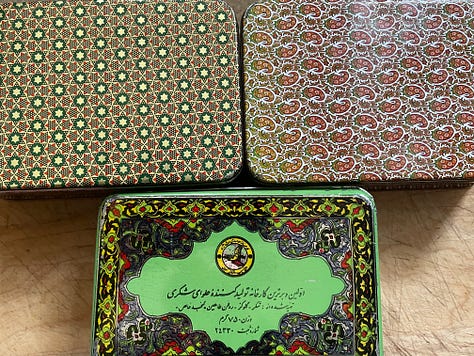

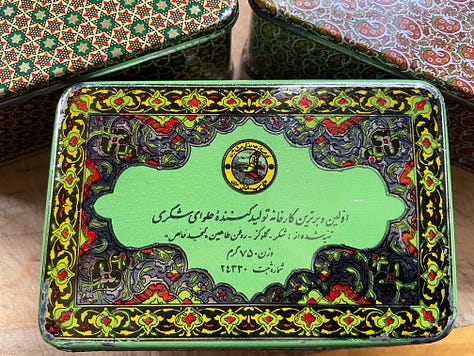

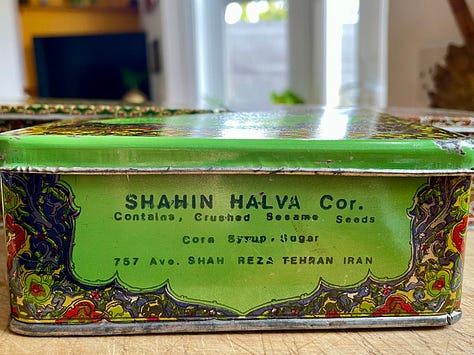

In Iran Tahini is known as ardeh which is described as sesame paste with oil. The most famous and popular tahini dish is halvaey arde which we Azeris call chunjut halvasi. Colourful metal tins of Shahin brand sesame halva with pistachio is the other thing which makes me smile. A couple of years ago I brought back an old tin mum used too keep buttons in (photos below). Shahin halva isn’t available anymore, this box is from the 70’s. The ingredient list on the box shows that even then it was made with corn syrup rather than soapwort extract1 traditionally used to make halva.

Mum usually buys achikh or open halva from the Grand Bazaar of Tabriz. They are sold in thin layers or blocks of tooth achingly sweet artisanal guri halva or dry halva and bought by weight from specialist kiosks run by halvachi. There are many varieties made with nuts, seeds and spices such as walnut, almond, sesame, bazirak (in Farsi) zaarayh2 (in Azeri) and ginger the famous delicate Azeri zanjafil tarayhi.

Halva or halweeat is the word for sweets in Arabic. In Azeri, we say the name of the specific halva as there are so many varieties. I mentioned a few of the dry halva above. Some are made and eaten on special occasions such as halva made for funerals or Ramadan (usually wet or tar halva).

When I was little we usually had fresh sanjayh for breakfast topped with various savoury and sweet toppings such as, cheese, sweet butter, cream, walnuts, jam, honey and halva. This was washed down with with mum’s blend of perfectly brewed boiling hot, crystal clear, carnelian coloured tea, filled to the brim of the thin glass istichan, (any less, and we’d be wondering why we’d been given half a glass).

Halva is quite sweet so mum would take a bite size piece of sanjayh to wrap around a morsel of feta cheese and halva to make a salty and sweet shor shirin ticha – by the way is where we get the word tikka you see on Indian menus meaning small pieces.

This up bringing has made me appreciate these simple pleasures. That I need my drinks to be just so, isn’t an affliction so much as a preference. I can’t eat a sweet thing without a hot drink and I can’t have a hot drink without a sweet (I’m trying to break this habit much to the surprise of my friends who always make sure they have or bake something sweet when I’m visiting). Also, I don’t like drinking out of thick glassware and I prefer my - non chai - hot drinks in large handled, bone china mug, except for my morning coffee. Cold drinks at room temperature and hot drinks, boiling hot, and to the brim. I believe these sorts of simple daily ritual are known as glimmers. Important, necessary and accessible daily joy.

Recently I fancied some halva. I thought I still had a small pack which I’d taken from the breakfast buffet from Hotel Homa earlier this year when mum and I went to Bandar Abbas in the Persian Gulf, but I’d eaten it. I recalled an intriguing recipe by the Palestinian food writer Reem Kassis5 whose work I’ve admired for years. Reem6 kindly granted me permission to use her recipe.

There are many methods for making halva. The traditional method requires very specific techniques, temperature and skilful mixing to get a good result. The recipe below is my version of Reem’s recipe. Simple store cupboard ingredients which you mix, press, rest, cut and eat with I hope, a well made hot drink in a perfect cup or glass.

By the way, I once ran out of tahini so I made my own. I did this by lightly toasting 4 tablespoons of seeds for 5 minutes on a medium heat in a dry pan, grinding it with a few drops of toasted sesame oil to make it smoother.

Chunjut halvasi – Sesame Halva

A few things to bear in mind about the recipe, depending on what is added to the brand of icing sugar, powdered milk and the dryness the nuts and powdered cardamom bring to mix, you will need to alter the amount of tahini for it to come together.

I’ve given a range for the tahini weight, start low and add a bit more if you need it. It might go into the fridge seeming a bit dry but comes out moist. Also be thorough but gentle in your kneading, you are trying to make every bit of the dry ingredients get coated in the oils of the tahini.

110g icing sugar - e.g. the brand I bought had: Tricalcium phosphate as the anti-caking agent.

120g milk powder I could only get skimmed – Reem uses whole milk powder.

200 - 240g* tahini - stir the jar thoroughly before adding.

1/8th tsp salt / soya sauce / white or yellow miso

¼ tsp of freshly ground slightly toasted cardamom more if it is mild

60g of lightly toasted pistachios – coarsely chopped – 50g Iranian slivered pistachios for decoration

Alternative additions: dark chocolate chips, crushed rose petals, lemon zest, strained and chopped candied peel to name a few.

Alternative flavours: rose or lemon oil and cocoa powder or vanilla paste.

I haven’t tried a dairy free version but I read you can use desiccated coconut instead of milk powder in this recipe. If you try it do let me know.

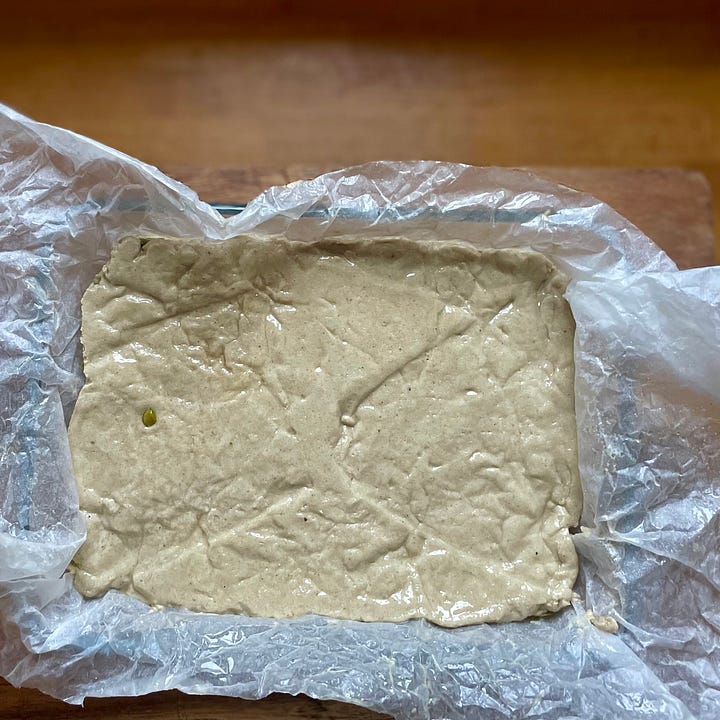

Start by lining your dish, the shape and size of the dish you press it into will depend on your preference if you’d like it thick or thin. I made mine in a (16 cm x 11 cm) dish, the halva was 2cm high. I used scrunched up parchment paper to line my dish as smoothly as I could, if you’d like a neater finish use plastic wrap. Pour whatever garnish like nuts or rose petals in, and then even it out all over the surface. Then thoroughly stir the tahini.

Now stir the sugar, milk powder, cardamon and salt, then add I added 200g of - well blended - tahini, stir it with a rubber spatula smooshing the mix against the sides of the bowl to make sure there were no bits of dry milk powder and it was all blended together. Then use your hand to bring it together like dough. If there is a lot of dry mix left in the bottom of the bowl, add another tablespoon or two of tahini and continue to bring it together. My mix needed a bit more so added another 25g (total 225g today). If add too much tahini and you feel it’s wet, you can add a little bit of milk powder to save it, but be careful. When it is holding together, press it into the dish.

I did this in two stages with an even layer of chopped and slivered pistachios as you can see in the photos. I lined and poured pistachio slivers into my dish, I gently pressed the dough in one layer to not move the garnish around too much then when it was even I applied more pressure. I then added the nuts and the rest of the mix. I pressed it again, wrapped it up, put another dish on it and weighed it down before putting it into the fridge.

I left mine overnight but 5 hours should be enough for it to be ready.Gently unwrap, then flip onto a plate. Mine was 510g this time.

It cuts neatly, I chose to cut the pistachio halva into 25 small pieces to pop in the mouth. It has a nut layer in the middle and would be awkward to bite into.

The crushed rose petal halva was leftover from last week. I took it to a birthday tea last Sunday and it was enjoyed by friends with very discerning palates who are great cooks. Two of them said it was the best halva they’d ever had.

You can make a double batch, press into several dishes, and decorate each with different garnishes. It will keep for at least a month in the fridge if it lasts that long. Allergens: Sesame & dairy.

If you enjoy this piece please let me know by tapping the ❤️ at the top or bottom or share — thank you.

“Open Sesame” from “Ali Baba and the forty thieves” in Harvey, W. (1973). Tales from the Thousand and one nights. Penguin Books.

Böck B., Ghazanfar S., Nesbitt M. (2023) An ancient Mesopotamian herbal Kew Publishing.

Herodotus. (1996). Herodotus: The Histories, London, Penguin Books.

Böck et. al. Ibid, 161.

R. Kassis (2021) The Arabesque Table: Contemporary Recipes from the Arab World, Phaidon Press

https://www.reemkassis.com/oldhome

fantastic post; i have just eaten, but am hungry again, craving hot tea and sth sweet... like you, i can't eat sweet without hot tea and vv. thank you

LOVE your very learned posts! didn't know we ould do sesame halva in our kitchen...